For more than ten years, healthcare workforce analysts have been sounding the alarm about an impending shortage of qualified nurses. Many healthcare experts have looked at nursing shortage statistics and offered analyses of the problem and how these shortages might be reduced.

For anyone interested in the current landscape of nursing, a first step is getting an understanding of 2022 nursing shortage statistics. Many factors are contributing to the current shortage, including the demographics of patient populations and nurses themselves, the limited capacity of accredited nursing programs and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Estimates of the number of registered nurses (RNs) in the U.S. range from 3,080,100 (Bureau of Labor Statistics) to 4,300,000 (the American Nurses Association). In either case, RNs make up the largest group of professional health care providers in the country. Despite the large numbers, however, shortages of qualified nurses in a particular state, region or hospital can have an impact on care delivery.

Let’s look at some current statistics and suggested solutions to see how the U.S. can best tackle the issue of its nursing shortage.

The Role of Demographics

When looking at nursing shortage statistics, it is important to understand the context for the shortage. A shortage occurs when the number of nurses available is lower than the estimated number of patients needing care in any setting—but particularly in hospitals, long-term care facilities and outpatient clinics. Experts agree that the large number of elderly patients in the population at large represents a challenge requiring a greater number of nurses.

In the broadest possible terms, the U.S. population is dealing with complex but advanced healthcare. Infant and child mortality rates are low and life expectancy is high, with an average of 78.9 years compared to the world average of 72.6 years. However, many older adults are experiencing multiple comorbidities that require ongoing nursing care, either in acute or chronic stages of the disease process.

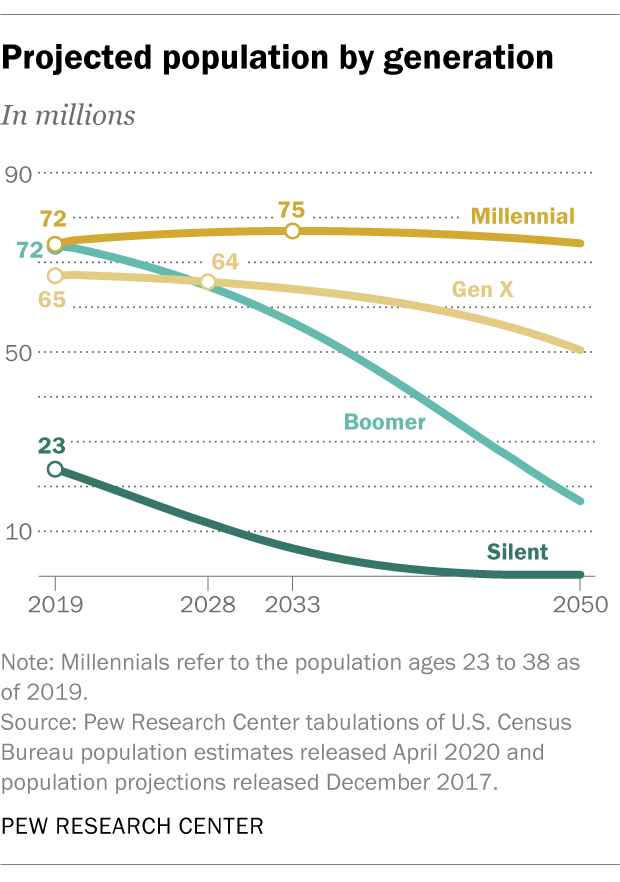

The number of older adults as a percentage of the population is rising quickly. Members of the baby boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1964), which was the largest population cohort for many years, are well into their retirement years.

According to the National Council on Aging (NCOA), about 85% of older adults have one chronic disease, and roughly 60% are dealing with two or more chronic ailments. The NCOA also states that two-thirds of all healthcare costs are associated with chronic diseases, and chronic diseases in older Americans represent 95% of their healthcare costs.

In 2019, the millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) overtook the boomers as the largest population group, and their healthcare needs are predicted to be problematic: A study by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Health Index predicts that millennials will be less healthy than Gen Xers (born between 1965 and 1980) as they enter older adulthood. The report cited a higher incidence of cardiovascular and endocrine conditions (including type 2 diabetes) among millennials compared to the rates among Gen Xers.

Nurse Retirements Contribute to the Shortage

Of course, nurses are members of these age cohorts as well. In 2020, the median age of RNs was 52, and a national survey conducted by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing and the National Forum of State Workforce Centers showed that more than 20% of registered nurses (RNs) were planning to retire within the next five years.

A slightly different perspective on the aging nursing workforce—one including nursing faculty as well as RNs—predicts that as many as one million nurses would reach retirement age in the next 10 to 15 years.

By any estimation, nurses aging out of the workforce is a significant factor in the ongoing nursing shortage.

The Impact of the Pandemic

Concerns about a shrinking pool of available RNs existed before the most recent challenge to healthcare: the COVID-19 pandemic. The novel coronavirus affected millions of Americans and sent hundreds of thousands of patients into the nation’s hospitals. Nurses and other healthcare workers had to contend with unprecedented numbers of hospitalized patients who had to remain isolated to limit the spread of the virus. All healthcare workers had to protect themselves from becoming infected, as well as minimize the risk of spreading the virus to vulnerable members of their households and community.

Nurses worked hard to deliver the best possible care to their patients. Nurses were reassigned to different departments to maintain coverage in the most critical care areas. But more than one million patients succumbed to the disease, sometimes with a nurse at their bedside holding a smartphone to allow patients to speak with their loved ones one last time.

With factors like the overwhelming numbers patient deaths, extra-long shifts and cutbacks among hospital support personnel, many nurses are experiencing high rates of job stress and burnout, leading to resignations and early retirement for some.

In a letter written in March 2022 to members of the Congressional Energy & Commerce Committee seeking assistance with the crisis, the American Hospital Association (AHA) outlined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, citing these statistics for the U.S.:

- 80 million COVID cases and nearly 950,000 deaths

- 4.5 million COVID-related hospital admissions

Furthermore, the AHA acknowledged the effect on nurses, saying:

“Nurses, who are critical members of the patient care team, are one of the many health care professions that are currently in shortage. In fact, a study found that the nurse turnover rate was 18.7% in 2020, illustrating the magnitude of the issue facing hospitals and their ability to maintain nursing staff. The same study also found that 35.8% of hospitals reported a nurse vacancy rate of greater than 10%, which is up from 23.7% of hospitals prior to the pandemic. In fact, two-thirds of hospitals currently have a nurse vacancy rate of 7.5% or more.”

Nursing Shortages in Rural Hospitals

By looking at the national estimates of nursing shortages, we see a broad picture. But when we zoom in to evaluate variances within states, a different picture emerges. For example, there have always been staffing differences between rural hospitals and those in or near major metropolitan centers. Rural hospitals have long had difficulty attracting health care personnel of all types, and RNs are in short supply there, too.

The pandemic has made this problem worse.

A November 2021 study of rural hospitals by Chartis Group, a healthcare industry consulting firm, stated that 98.5% of the respondents were experiencing a staffing shortage, with 96.2% saying that RN positions were the most difficult to fill. Furthermore, the nurse shortages were forcing nearly all of the surveyed hospitals to deny new admissions and about 30% of them to suspend certain services.

Some rural hospitals have brought on travel nurses to fill some nursing staff gaps. This is a temporary—and very expensive—solution for RN staff shortages. Typically, assignments for travel nurses last 12–13 weeks and pay about four times the average pay rate, depending on the nurse’s focus area.

RN Shortages Vary by State

Nurse shortages may be critical in one state and less dire in another. A report from the Department of Health and Human Services that projected nurse workforce needs out to the year 2030 identified which states would have the greatest shortages based on population projections and factors such as desirable locations for retirees, who would make a greater claim on health care services.

States with the highest projected RN shortages for 2030

| Projected Supply | Projected Demand | Difference | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | 343,400 | 387,900 | -44,500 | (11.5%) |

| Texas | 253,400 | 269,300 | -15,900 | (5.9%) |

| New Jersey | 90,800 | 102,000 | -11,400 | (11.2%) |

| South Carolina | 52,100 | 62,500 | -10,400 | (16.6%) |

| Alaska | 18,400 | 23,800 | -5,400 | (22.7%) |

| Georgia | 98,800 | 101,000 | -2,200 | (2.2%) |

| South Dakota | 11,700 | 13,600 | -1,900 | (14.0%) |

Source: Supply and Demand Projections of the Nursing Workforce: 2014–2030

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis

The Shortage of Nurse Educators

Another factor contributing to the shortage of RNs happens not at the end of their careers, but before they can even get started. Currently, many nursing schools around the country lack enough qualified nurse educators. Low faculty numbers mean that fewer students can be enrolled each semester, limiting each year’s pool of new graduates.

The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) issued a report stating that more than 80,000 nursing school applicants were turned away from bachelor’s and master’s programs in 2019 because of an “insufficient number of faculty, clinical sites, classroom space, and clinical preceptors, as well as budget constraints.”

Faculty shortages mean fewer RNs entering the clinical workforce, but it also means fewer spaces are available for nurses who want to be prepared at the doctoral level so they can go on to become faculty themselves.

The Need for Nurses and Nurse Practitioners in Special Roles

While nurses in all roles are needed, nurses and nurse practitioners (NPs) with focused graduate level education and/or certification in certain areas will be in high demand.

- Adult/Gerontology Primary Care. RNs and NPs who have focused their education on the mental and physical needs of elderly patients are needed to help with the increasing numbers of aging Americans.

- Critical Care Nurse. Critical care RNs care for patients that require advanced management for life threatening conditions. They commonly work in the intensive care units. Advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) certified in critical care can also serve patients in critical condition. This type of APRN is frequently assigned to an intensive care unit (ICU) where they diagnose and manage complex and often life sustaining interventions needed for critical and complex illnesses.

- Labor and Delivery Nurse or Certified Nurse Midwife. Helping mothers and newborns in the process of labor, delivery and recovery is an important role for an RN. APRNs certified as nurse-midwives care for women throughout pregnancy as well as during delivery.

- Psychiatric Nurse or Psychiatric/Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (PMHNP). Psychiatric nurses are needed on mental/behavioral health care teams who are treating patients with a variety of issues, such as mental illness, eating disorders or addiction. P/MHNPs provide mental health services to patients, including care management and prescribing medication.

Consequences of the Nursing Shortage

Experts and organizations who warn about nursing shortages are doing so because the primary consequence of overworked or inadequate numbers of nurses is the risk of adverse patient outcomes. Studies have shown that when optimal nurse-to-patient ratios are exceeded, the risks to patient safety increase, with higher rates of pneumonia, nosocomial infections, falls, decubitus ulcers and, in the worst cases, failure to rescue and death.

Shortages of nurses also increase the risk of nurse burnout, as they experience compassion fatigue—a lack of emotional connection to patients that can result from physical, spiritual and emotional stress—as well as pure physical fatigue as nurses are required to take on tasks that were once performed by support personnel.

COVID-exacerbated nurse shortages also contribute to longer wait times for patients arriving in emergency rooms throughout the country. President of the Emergency Nurses Association Ron Kraus, MSN, RN, says, “The pandemic has only amplified several long-standing issues impacting emergency nurses, such as workplace violence, a healthy work environment, and concerns about staffing shortages and the pipeline of new nurses. That said, we can't lose focus on what’s most important in these challenging moments―ensuring every patient receives the high quality of care.”

Nursing Shortage Solutions

Plans that were underway to address the nursing shortage before the pandemic now need to be expanded and prioritized.

- To address the supply problem at its source, there is a need to graduate more qualified masters and doctorally prepared nurse educators, which will in turn allow for increased enrollment of nursing students.

- Expand access to education for current and aspiring nurses by providing scholarships and loan forgiveness to nursing students, as recommended by the AHA. Other programs include the formation of strategic partnerships between university nursing programs and states, foundations and other entities to expand enrollment.

- Advocate for a healthier environment for nurses. A work environment that addresses nurses’ concerns—both professionally and personally—will help nurses remain in their jobs with a greater sense of control and support. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses states, “Healthy work environments are safe, healing, humane, and respectful of the rights, responsibilities, needs, and contributions of all people—including patients, their families, nurses, and other healthcare professionals.”

You Can Commit to a New Nursing Career

If you are considering entering the nursing profession as an RN, or if you are an RN who wants to pursue a new role, online nursing programs at Wilkes University can prepare you to take the next step.

- An Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing is designed for people who already have a bachelor’s degree in a non-nursing field. The program can prepare you to become a registered nurse in just over one year.

- Master of Science in Nursing (MSN). Wilkes has several master’s programs designed to meet the needs of nurses (or non-nurses) who want to pursue a focused nursing practice including advanced practice registered nurse specialties.

- The Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) degree is typically pursued by those who already have an MSN and who seek a terminal degree focused on clinical care or a leadership role.

- A Post-Graduate/APRN Certificate is geared toward current RNs or NPs who hold a MSN and want to master clinical skills with a specific care focus, such as Family Nurse Practitioner, Adult-Gerontology Primary Care or Psychiatric/Mental Health.

- A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Nursing is the other terminal degree in the field. With a focus on research and scientific inquiry, the PhD can prepare you to advance the nursing profession through scholarship.

You can be a part of the solution for the current nursing shortage. Find out how to get started with an online nursing degree from Wilkes University.